GCSE Macbeth

Soliloquies – Macbeth

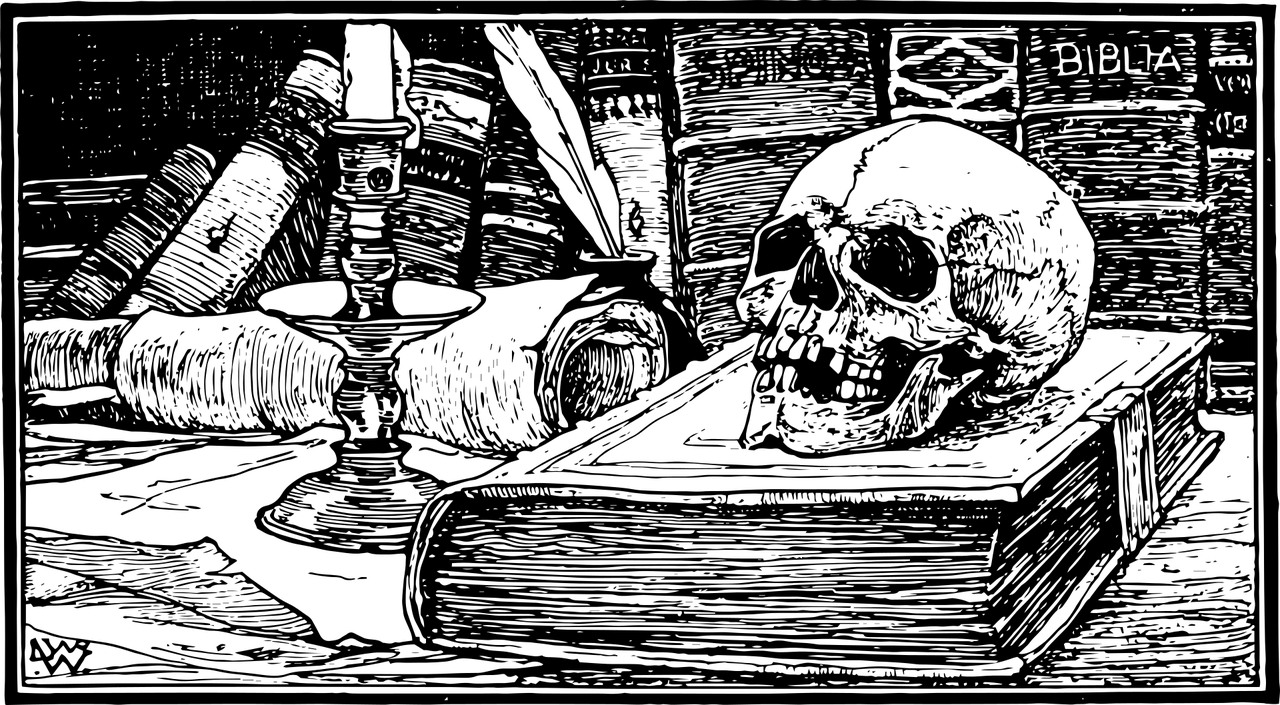

“Is that a dagger I see before me?”

William Shakespeare’s Macbeth has it all: murder, ambition, jealousy, revenge … but where to begin when it comes to getting to grips with the so-called ‘Scottish play’ for GCSE? Our senior tutor in English, Sara Di Fagandini, explains how to get the most from this most challenging yet rewarding of Shakespeare’s plays.

Studying Shakespeare can be overwhelming. Aside from the difficulties presented by 400-year-old writing, there are themes to remember, quotations to memorise… So, if you find you’re struggling with Macbeth then don’t panic, because you’re not alone.

When it comes to revising for Macbeth, I always advise my own students to make sure that they know the key characters really well and suggest that they compose an Act Overview to help prepare for the exam. Unlike some of the other papers, context for Macbeth is super important in helping you to understand and interpret the play, so make sure you’re clued up on the key themes of the play, as well as what was going on in English and Scottish history. It is also important to understand Elizabethan attitudes towards witchcraft and the supernatural.

When it comes to picking out quotes and themes, I tend to steer students towards the soliloquies, where characters speak their thoughts aloud and give the impression they’re talking to themselves. Macbeth has eight, and each provides a fantastic insight into the speaker’s development, psychology and motivations, making them brilliant for quotations.

Soliloquy 1: Macbeth reflects on the witches’ prophecy. 1.3 (l. 240-255)

Having just learned of the witches’ prophecy, Macbeth is clearly terrified. He speaks of the temptation to become king (‘This supernatural soliciting’, l.129 – note the repeated and sinister ‘s’ sounds, known as sibilance), but senses that his instincts are somehow wrong: ‘why do I yield to that suggestion // Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair // And make my seated heart knock at my ribs… ’ (l. 133-135). His suspicions that his ideas are in some way “unnatural” prefigure other unnatural events later in the play, for example the perpetual darkness after Duncan is murdered.

Soliloquy 2: Lady Macbeth learns of the witches’ prophecy. 1.6 (l. 35-52)

There are few Shakespearean antagonists more chilling than Lady Macbeth, and her opening soliloquy, where she reads the letter from her husband, is a masterstroke in psychological characterisation. Cold, ruthless, remorseless, Lady Macbeth’s key quotes include ‘unsex me here’ (l.39), setting up the subsequent swapping of gender roles within the Macbeths’ marriage, and the images of darkness in lines 48-52, where she evokes ‘the dunnest smoke of hell’ so that it may hide her hand as she stabs Duncan.

Soliloquy 3: Macbeth, having agreed to kill King Duncan, has a change of heart. 1.7 (l.1-28)

Convinced by his wife to murder Duncan, Macbeth now has a change of heart, echoing his uncertainty during his first soliloquy. Here, he reveals his fear that the assassination will lead to problems for him, concluding that his ‘vaulting ambition’ (l.27) will cause him to overshoot his mark, spelling disaster. The contrast – or juxtaposition – between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in this scene further emphasises Macbeth’s growing emasculation, and how it is Lady Macbeth who is in charge.

Soliloquy 4: ‘Is this a dagger I see before me…?’ Macbeth sets his intentions to kill King Duncan. 2.1 (l.33-64)

One of the play’s most famous soliloquies, Macbeth imagines that he sees a dagger in front of him which leads him to kill Duncan. He questions the dagger, anthropomorphising it by asking it questions (‘Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible // To feeling as to sight?’, l.36-37). Take note of the final couplet, where the strong rhyming of ‘knell’ and ‘bell’ (l.63-64) suggests certainty or conclusion: Macbeth’s mind is made up and he will definitely go to kill Duncan.

Soliloquy 5: Macbeth expresses his concerns towards Banquo. 3.1 (l.48-73)

It’s rare for this one to up in exams, but make sure to take note of Macbeth’s growing suspicions towards Banquo (‘They hailed him father to a line of kings’, l.61) – not to mention the advertising plug for Shakespeare’s other tragedy, Julius Caesar, which had its first performance only a few years before Macbeth, in September 1599.

Soliloquy 6: Macbeth plans to murder Macduff’s family. 4.1. (l.160-70)

As we move into the later stages of the play, Macbeth’s behaviour becomes increasingly erratic and difficult to predict. In this short speech, he lays out his plans to murder Macduff’s family, finishing on another rhyming couplet (‘fool’ and ‘cool’, l.169-170) to indicate his intentions are set.

Soliloquy 7: Macbeth makes peace with death. 5.3. (l.20-30)

Calling to Seyton, his servant, Macbeth reveals his belief that the upcoming battle against Macduff will either make or break him as a ruler: ‘This push // Will cheer me ever or disseat me now’ (l.21-22). Note the pun – actually a homophone – on ‘disseat’ (meaning to unseat or dethrone) and ‘deceit’ (meaning trickery or deception). In this short speech, Macbeth appears to come to terms with his own death, saying ‘I have lived long enough’ and claiming that he does not wish to live to old age (which he compares to a ‘yellow leaf’, l.24, tying in with one of the play’s key themes – nature and the natural world).

Soliloquy 8: ‘Out, out brief candle.’ Macbeth prepares himself for his death. 5.5. (l.17-27)

With news of Lady Macbeth’s death, and sensing that defeat is near, Macbeth speaks about the futility (pointlessness) and transience (briefness) of life, making a link between theatre performances and life itself (‘Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player // That struts and frets his hour upon the stage’, l.23-24). The line ‘tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow’ (l.18) is an excellent use of the literary device polysyndeton combined with caesural pauses, which stretch out the three ‘tomorrows’, suggesting that Macbeth is tired of the monotony of living.

All line references are taken from the Norton Shakespeare International Student Edition.

Get in Touch

-

Give us a call

020 8883 2519 -

Email us

hello@mentoreducation.co.uk -

Our social media